Multiple Vehicle / Multiple Casualty Incidents

Multiple vehicle and multiple casualty incidents are thankfully rare but do happen. In my career, I attended three such incidents and for two of those three, I was on the first vehicle in attendance. That is of course not counting the motor racing incident I wrote about in Blog 74!

Upon arrival at these incidents it is immediately obvious that they are likely to be a ‘Major Incident’. Each agency and indeed each country will work to different definitions of exactly what a major incident actually is, but the underlying theme in all definitions is one of the immediate response capability being completely overwhelmed with a need for extra resources.

Incident Information Model

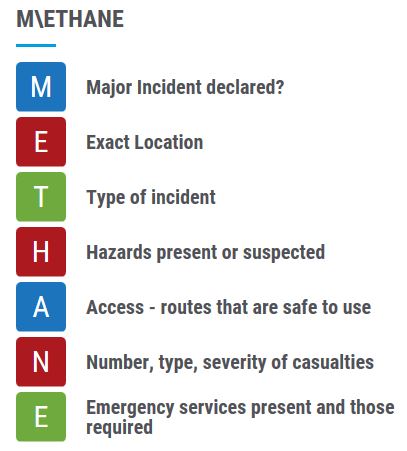

That has always been the case in my personal experience and the initial priority is to establish some basic information which can form your decision regarding what has happened, who is involved and who/what else is required on scene. In recent years the JESIP (Joint Emergency Services Interoperability) Program in the UK has used a mnemonic for communication between emergency agencies on scene and I would recommend taking a look at M\ETHANE.

How it works

Strategically, incident commanders, upon arrival, should use the M\ETHANE model (or similar) to formulate their first communications from the scene. This will immediately trigger any major incident protocols from all agencies and provide important information for resources that will attend the scene e.g. safe access routes and rendezvous points and number/severity of casualties.

Practical points

From a practical point of view, arriving first on scene of a multi-vehicle crash crews must establish the following:

- Adopt a safe system of work by identifying, communicating and controlling hazards

- Order extra resources immediately

- Identify casualties and initiate a triage protocol

- Utilize resources based on triage results

Moral dilemma

It may well be that at this point (depending upon numbers of rescuers available) you simply may not be able to do anything more than patient care. Unfortunately, this may also involve not being able to treat every casualty on scene until further resources arrive. This is a difficult moral dilemma and one that is difficult to prepare for; you must simply do your best.

Deployment

When extra resources arrive it then becomes a case of using them based on the initial and ongoing triage; identify the most time critical patients and deploy as necessary. In the UK, there is a ‘sectorization’ protocol which essentially splits a large scene up into more manageable ‘sectors’, each with their own command team who report to the overall incident commander. If this is something you do not currently do, it is worth considering. Rescue tools and equipment may have to be positioned so that multiple crews can access them and communication here is key so as not to delay already difficult extrication operations.

More doctors

We must unfortunately consider that incidents such as these will massively affect our extrication times, simply due to their large nature. This has to be considered by the medical agencies too, when pre-planning for major incidents. This delay will mean that rather than the patient getting to hospital in a timely manner as with smaller, less complex incidents, the hospital has to come to them. This is often reflected in a major incident protocol by the attendance of more doctors.

Conclusion

Multiple vehicle and multiple casualty incidents test everyone’s resilience, both personally and from an organizational perspective. The key is training and pre-planning, not in isolation but with all agencies involved.

Quite simply, it comes down to training.

As ever, I welcome your comments!

Ian Dunbar